By Richard Jack, Global Market Development Manager of Food and Environmental at Phenomenex, and Craig Butt, Manager of Applied Markets, Strategic Global Technical Marketing at SCIEX

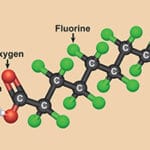

The past decade has seen a seismic shift in awareness around per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, known as PFAS. They have transformed from a class of chemicals used in manufacturing into an ecological and public health crisis. PFAS have been manufactured since the 1950s and are in widespread use. The main challenges we have include understanding the prevalence of the many possible varieties of compounds, how they get into our bodies, and what harm they might cause. When scientists began testing air, water, and soil for the presence of these “forever chemicals” (so named because most PFAS don’t degrade readily in the environment), they found PFAS everywhere they looked. From the remote Canadian Arctic to the deepest depths of the oceans, PFAS were there.

It’s not just their ubiquity. A growing number of research studies are showing that PFAS pose significant health and environmental risks. PFAS have been linked to everything from asthma and liver damage to fertility problems and cancer. Regulatory agencies in Europe and the United States have begun placing statutory limits on PFAS in drinking water and in consumer products. These efforts join calls from the public for companies to reduce or eliminate PFAS in the products they make. Punctuating their concerns are a flurry of lawsuits against manufacturers of PFAS compounds, such as E.I. du Pont de Nemours, 3M, Chemguard, and many others.

Improvements in instrumentation and testing methodology mean that scientists can now measure ever-decreasing concentrations of PFAS. Detection limits now hover in the parts-per-trillion or per-quadrillion range, which approximates the ability to detect a drop of water in Lake Michigan. These new limits of detection, combined with studies linking harms to increasingly lower PFAS concentrations, mean that many manufacturers, especially those in the food and beverage industry, are facing new concerns about whether and how to test for PFAS.

A backdrop of ever-shifting regulatory rules and potential litigation means that choosing the right testing partner is more important than ever before. A skilled PFAS testing company will have experience with testing for low levels of PFAS in general and will know which specific PFAS to analyze for and how to choose the most appropriate techniques. Their in-depth expertise means that they will provide guidance on the latest legal requirements and industry best practices that will help guard against potential risks to your business.

Who should test for PFAS?

The near universality of PFAS compounds makes it hard to identify a company that doesn’t need to test for PFAS in their products. One of the earliest known sources of PFAS – and presumably also best publicized in the popular media – was microwave popcorn bags. Because food and beverage manufacturers make products that consumers ingest, the testing of these products is especially important. Consumer concern is reflected in recent litigation and in new laws passed in Massachusetts and California banning PFAS in food packaging. As a result, many fast-food chains, grocery chains, and food retailers have committed to removing PFAS compounds from their food packaging.

A major challenge to testing for PFAS in foods and beverages is identifying how they got in the final product. Sewage sludge used on agricultural products, water that rinses equipment, and packaging used in transport can all lead to PFAS in the food we eat and liquids we drink, which can make it hard to narrow down where PFAS came from and how to get rid of them. However, casting a wide net means that companies will be able to identify all potential avenues of contamination. This is crucial if and when your organization decides on actions to reduce PFAS, such as finding alternate vendors or modifying manufacturing. These steps are possible only when you know how much PFAS you have and how they are getting into your product.

Seek out technical expertise

Growing awareness of PFAS contamination has meant a simultaneous increase in the number of labs offering PFAS testing services. Current testing requires PFAS extraction and clean up prior to detection and identification. The extraction is best performed using a technique known as QuEChERS, followed by solid phase extraction (SPE) for concentration and further cleanup. Then, the extracts are ready for detection using liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry (LC-MS). Liquid chromatography (LC) columns serve to separate the different components of each mixture, while mass spectrometry (MS), a type of chemical detector that uses the mass and charge of a compound to pinpoint its identity, remains the industry’s gold standard for identification due to its specificity and sensitivity. This means that MS is not only good at identifying PFAS in various products, but it also makes false positives unlikely. Investing in the use of sensitive analytical tools, like mass spectrometry, will help industry executives identify chemicals and address contamination issues.

Improvements in both LC and MS mean that scientists can now detect even the tiniest amounts of PFAS, which creates an additional problem for testing companies. This means that PFAS cross-contamination with reagents and environmental factors can create the illusion that PFAS is in a product. Testing companies with adequate expertise will have advanced training for laboratory technicians, along with laboratory precautions and appropriate sample cleaning methods. This can dramatically reduce headaches later.

With as many as 5,000 different PFAS chemicals in use, identifying individual compounds, such as GenX or perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), can be challenging. If you know of specific PFAS chemicals that might be in your product, you can perform targeted testing, looking for just a small handful of compounds. But LC-MS can also be used in untargeted testing, which allows you to find PFAS chemicals that you didn’t know were there. With so much PFAS contamination in the environment, it’s entirely possible that PFAS can wind up in the final product without it being on an official list of ingredients or raw materials. Identifying these “hidden” sources of contamination is extremely important because it signals to the consumer that you take their health and safety seriously.

Don’t forget sample prep

With so much attention being paid to the technical aspects of PFAS testing and its position in the regulatory environment, it’s easy to forget that testing partners can also help with one of the most labor-intensive parts of testing: sample prep. It might not sound like a major issue from the executive suite, but quality testing companies know that sample prep is key to obtaining accurate results and it can also be one of the largest costs for testing companies.

Products related to food and drink are not uniform and can create a variety of challenges in PFAS testing. The different matrices in which PFAS may be embedded, such as meat, produce, or packaging, require different approaches to prepping and cleaning the sample before testing. It is important to ensure that your testing partners have adequate experience working with the types of products you need tested. There are also ready-made kits that can perform sample prep and cleaning in one step, saving valuable time and money.

Document best practices

Testing partners with a long history of working with regulators and industry guidelines will also be up-to-date on the latest rules from regulators including the EPA and the FDA about validated testing methods and (in the future) what levels of PFAS are permitted in a product. They also need to be familiar with industry best practices for testing. While this may not prevent a potential lawsuit, being able to provide evidence that you followed the best and most current guidelines for testing and remediation might help when it comes time to litigate the suit. Due to the potential threat of litigation, it’s important to ensure that a testing partner can provide adequate documentation of the precise tests that they are performing and how these tests measure up against industry best practices.

Consumers are beginning to demand that the companies making their food and drink are doing everything possible to reduce and eliminate PFAS. A rigorous testing program is the first step towards identifying potential contaminants. Then, a company must determine what to do. Some steps may be relatively easy and painless; others may take more time and investment. Being able to document and share these steps will allow you to tell shareholders and consumers alike, “Here’s what we’re doing about PFAS.”

The chemical nature of these forever chemicals means that PFAS contamination is not going to disappear overnight. This means that you might have a long-term, committed relationship with your testing partners. Doing your homework at first to find the right expertise will help create a partnership you can rely on.

Richard Jack, Ph.D., is the Global Market Development Manager for the Food, Cannabis and Environmental Markets at Phenomenex. Richard has nearly two decades of experience in product and market development in the analytical sciences industry, including as a former EPA Scientific Advisor developing validated methods through new applications, instrumentation, column chemistries, and software. Richard received his M.S. in Ecology from the Univ. of TN, Knoxville, TN. and his Ph.D. in Biochemistry and Anaerobic Microbiology from VA Tech in Blacksburg, VA.

Craig Butt, Ph.D., is the Senior Staff Scientist, Food/Environmental, Global Technical Marketing at SCIEX. He puts over 20 years of mass spectrometry experience to work developing groundbreaking MS methods for the environmental chemistry and toxicology of PFAS and persistent organic contaminants. He obtained his PhD in environmental chemistry at the University of Toronto where his thesis research investigated the fate of PFAS in biological systems. He was an NSERC post-doctoral research fellow in the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University, later becoming a research scientist in the department.